Campania electorala e construita pe niste tactici in care incerci sa faci ca mesajul tau sa ajunga la cat mai multi oameni, iar in asta intra mai ales in Romania, sa scriticam ce face contacandidatul si mai purin sa spunem ce planuri avem noi si ce proiecte de dezvoltare.

Pe mine ma deranjeaza tare cand in campania electorala candidatii se trezesc sa se ia de familia contracandidatilor. Si cand observatiile urate si atacurile vin de la o femeie candidat, care ar trebui sa fie mult mai protectatore cu ideea de familie, totul are un iz oribil.

Am avut-o acum ceva ani pe doamna firea care s-a trezit sa comenteze ca e urat ca familia Iohannis nu are copii, iar cateva zile mai tarziu a inventat ca fostul presedinte s-a ocupat de adoptii internationale si vindea copii samsarilor. Ceva absolut oribil si inutil in dezvoltarea unor idei pentru campania electorala.

Dar pentru publicul roman, orice mizerie e un prilej de ura si injuraturi, chiar si nefondate.

Aseara doamna Lasconi, care e oricum suparata ca au abandonat-o colegii din USR si are probleme mari logistic pentru finantarea si organizarea campaniei, a comentat ceva foarte foarte urat despre Nicusor Dan.

A spus ca primarul capitalei nu isi iubeste copiii, ca l-a avuzit dansa in nu stiu ce emisiune povestind ca nu le spune copiilor foarte des ca ii iubeste si ca fetita dansului i-a cerut sa-I spuna mai des te iubesc.

Evident a facut ricoseu catre dansa si ne-a spus cat de mult iubeste dansa copiii, si propria familie.

Comentariul e josnic. Nu ajuta la nimic si nici nu e real, fiind de notorietate ca Nicusor Dan isi organizeaza pauza de masa la primarie ca sa se duca sa-si ia fetita de la scoala si sa o duca acasa, sa petreaca la pranz putin timp impreuna. Plus ca peste ani toata lumea a vazut ce familie frumoasa , cu bun simt si modestie, are primarul care acum candideaza la prezidentiale.

Chiar daca familia Dan comunica foarte putine detalii personale ( e si normal pentru ca isi doresc ca fata si baiatul sa traiasca ca niste copii normali, in ciuda expunerii tatalui ), primarul a mai povestit comentariile comic ironice pe care le face cea mica (are acum 9 ani), despre cum se imbraca tatal ei, despre cum ii sta parul si alte lucruri simpatico din orice familie normala care arata o atmosfera calda si frumoasa.

Revenind la doamna Lasconi si remarca dansei absolut oribila, nu inteleg ce urmareste cu asemenea mizerii. De ce sa faci asa ceva cand stii si ca nu e adevarat, dar mai ales cand ai trait chiar tu durerea judecatii publice in relatie cu fiica, la momentul cand aceasta a marturisit ca apartine comunitatii LGBTQ+.

Consilierii doamnei Lasconi – daca i-a mai ramas cineva in echipa – invatati-o ca-si face rau… nu o ajuta cu nimic sa zica mizerii despre familiile contra candidatilor.

Sigur ca astazi candidatii nu mai pun pret pe etica si sunt pe principiul “pe cadrave inainte”, dar mi se pare important sa stiti ce e etic si ce nu (si va las mai jos si cateva carti, daca vreti sa dezvoltati subiectul).

Mi se pare ca am trecut printr-un soc asa de mare odata cu anularea alegerilor incat ar trebui sa folosim momentul sa reasezam totul pe valori corecte, ca sa nu ne mai lasam influentati de toate mizeriile de la tv.

Intr-o campanie electorala etica si civilizata, felul in care un candidat se raporteaza la familia contracandidatului este extrem de important. Cum intr-o alta viata am invatat despre comunicarea in campaniile electorale, iata ce este etic si ce nu este etic din punct de vedere al bunei conduite politice.

Ce este etic sa faca un candidat:

Sa pastreze discutia asupra ideilor si performantelor politice, nu asupra vietii private a contracandidatului sau a familiei acestuia.

Sa nu implice familia adversarului in discursul electoral, decat daca este intr-un mod obiectiv, verificabil si legat de chestiuni de interes public (ex: daca o ruda a fost numita intr-o functie publica intr-un mod care ridica semne de nepotism, si asta e dovedibil).

Sa condamne public atacurile josnice venite din tabara sa la adresa familiei altor candidati (daca ele apar) – este o dovada de integritate si de leadership real.

Sa evite sarcasmul sau aluziile personale – chiar si glumele aparent nevinovate despre familia unui contracandidat pot fi percepute ca atacuri murdare.

Ce nu este etic (si poate fi sanctionat de opinia publica):

Atacuri la persoana care implica membrii familiei – mai ales daca acestia nu au nicio implicare politica. Exemplu: ironizarea sotului/sotiei pentru cariera, aspect, viata personala.

Scotocirea vietii private in cautare de vulnerabilitati – folosita in mod intentionat pentru discreditare (ceea ce se cheama campanie negativa murdara).

Dezinformarea – promovarea de zvonuri sau acuzatii false legate de familia contracandidatului (chiar si cu formulari ambigue sau insinuante).

Implicarea copiilor contracandidatului – acest lucru este considerat grav, mai ales daca acestia sunt minori. Este un consens larg ca minorii trebuie protejati de orice atac politic.

Principiul de baza in etica electorala: “Ataca ideile, nu oamenii. Mai ales nu pe cei care nu candideaza.”

In Romania, nu exista o lege care sa interzica explicit aparitia membrilor familiei intr-o campanie electorala. Cu toate acestea:

Legea 334/2006 privind finantarea activitatii partidelor politice si a campaniilor electorale reglementeaza clar cheltuielile si resursele implicate, dar nu specifica norme despre familie.

CNA poate interveni daca se considera ca un spot TV cu minori, de exemplu, incalca drepturile acestora sau normele de difuzare.

La alegerile din 2014, Victor Ponta si-a folosit propriul copil in campanie, aparand cu fiul sau minor la acea vreme in spoturi si fotografii oficiale. Acum Victor Ponta a dus-a la emisiune la Marius Tuca, pe cea mai mica dintre fiicele sale (si ea minora)sub pretexttul ca ea a vrut sa-l insoteasca ca sa-i ureze succes.

In 2014 nu a existat o sanctiune, dar a fost o tema de discutie in presa si in societatea civila, astaziz ne-am obisnuit atat de ult cu expunerea vietilor private incat nu ne mai gandim ca e o forma de manipulare.

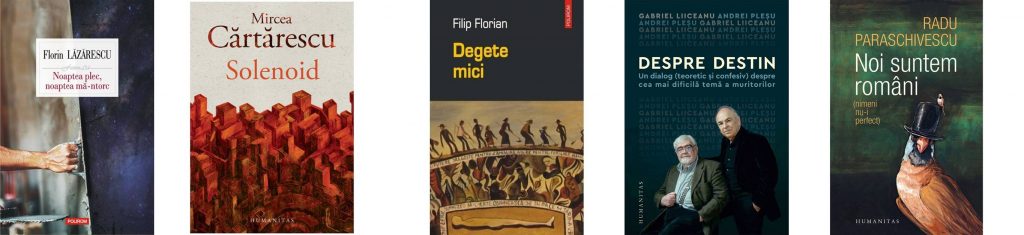

Avem cateva carti foarte relevante care trateaza subiectul etica in campaniile electorale, inclusiv aspectele legate de viata privata, familie si conduita candidatilor.

„Etica si politica” – Michael Sandel. Nu e despre campanii in mod direct, dar trateaza fundamentele eticii politice si cum ar trebui sa se comporte oamenii publici. Excelenta pentru intelegerea diferentei intre moral si legal.

“The Ethics of Political Communication” – Peter J. Schulz & Hartmut Wessler. Abordeaza cum se comunica etic in campanii si care sunt limitele discursului politic.

“Dirty Politics: Deception, Distraction, and Democracy” – Kathleen Hall Jamieson. E o lucrare de referinta in analiza manipularii electorale. Trateaza direct folosirea vietii personale a candidatilor.

In „Dirty Politics: Deception, Distraction, and Democracy” doamna Kathleen Hall Jamieson scrie despre politica murdara caren nu inseamna neaparat minciuna – ci distorsionare. Ea arata ca cele mai eficiente tehnici de manipulare nu sunt neaparat fake news evidente, ci adevaruri spuse pe jumatate, scoase din context sau prezentate cu intentie inselatoare.

Exemplu: Un clip care arata ca un candidat „a votat impotriva cresterii pensiilor” poate ascunde faptul ca proiectul de lege era unul toxic in alte privinte.

Tot in aceast carte e abordata distragerea atentiei de la teme importante. Campaniile murdare functioneaza prin deturnarea dezbaterii publice. Se arunca teme controversate (viata personala, familia, zvonuri) tocmai pentru a evita discutiile reale despre politici publice. Aceasta e o strategie de tip “look over here” – creezi scandal ca sa eviti explicatiile incommode, se mai numeste si “tehnica steguletului” – fluturi un steag intr-o directie ca sa distragi atentia de la ce e important cu adevarat.

Jamieson arata cum atacurile personale sunt mai eficiente decat cele pe idei.

Psihologia umana reactioneaza mai puternic la mesaje emotionale decat la cele rationale. Din aceasta cauza, campaniile murdare tind sa aiba impact electoral mai mare, chiar daca sunt lipsite de continut.

Aceasta idee este dureroasa dar realista: alegatorii nu sunt mereu rationali.